Franz Reindl «STRATEGIES AND TECHNIQUES FOR AUGMENTING THE POPULARITY OF INTERNATIONAL ICE HOCKEY COMPETITION»

Sergey Altukhov, Vladimir Ageev «ICE HOCKEY IN CHINA: RUSSIAN ROLE IN CHINA’S ICE HOCKEY MARKET DEVELOPMENT»

Young Hoon Kim «IS ICE HOCKEY ON THE RIGHT TRACK IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA?»

Jyri Backman «ICE HOCKEY ORGANIZATION AND INNOVATION IN SWEDEN AND FINLAND»

Guillaume Bodet «WHO ARE THEY? A FOCUS ON FRENCH ICE-HOCKEY PARTICIPANTS’ PROFILES»

Hongxin Li , John Nauright «THE KUNLUN RED STAR PHENOMENON AS A CASE STUDY FOR HOCKEY GROWTH IN ASIA»

Liangjun Zhou «HOW TO PROMOTE THE DEVELOPMENT OF ICE HOCKEY IN CHINA AND OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES? A CASE STUDY OF GUANGZHOU»

Vladimir Ageev, Sergey Altukhov «ICE HOCKEY IN THE METROPOLIS: A SUPPLY AND DEMAND ANALYSIS FOR ICE INFRASTRUCTURE IN MOSCOW»

Daniel Mason «CITIES, INVESTMENT, AND THE ICE HOCKEY DREAM: LESSONS FROM CANADA»

Dongfeng Liu «ICE HOCKEY DEVELOPMENT AND PROMOTION STRATEGIES IN CHINA»

John Nauright, Zachary Beldon, Hongxin Li «NEW MARKETS FOR ICE HOCKEY: HOCKEY IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES»

Igor Baradachev «HOW TO MAKE ICE HOCKEY APPEALING FOR CHILDREN»

Julie Stevens «HOCKEY’S “INNOVATION CRISIS” AND THE NEED TO DEVELOP HOCKEY TALENT FOR THE FUTURE: THE CASE OF CANADIAN MALE HOCKEY»

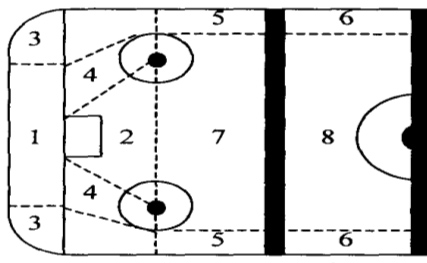

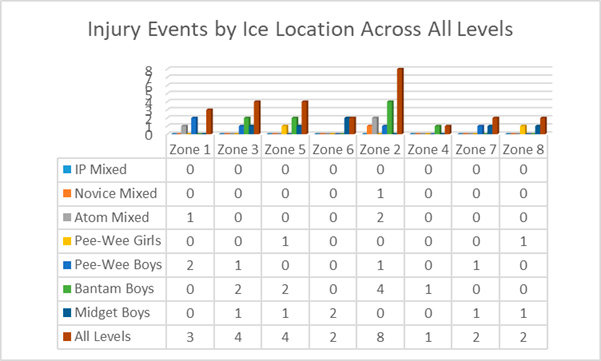

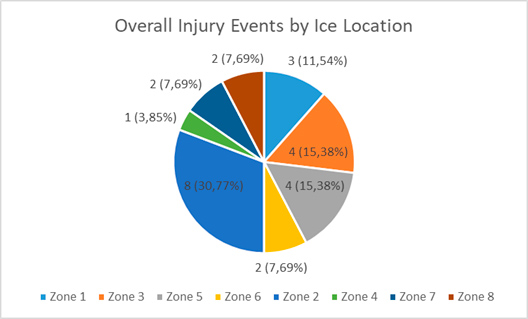

Michael A. Robidoux «OBSERVATIONAL ANALYSIS OF INJURY EVENTS ACROSS»

Alexander Martynov «ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AT WORK IN HOCKEY INDUSTRY»

Bruno Marty «THE MEDIA LANDSCAPE IS EVOLVING AND TRADITIONAL MEDIA REMAINS STRONG»

Franz Reindl, IIHF Council member and President German Hockey Federation (DEB).

“Hockey is my passion and I really want to help to develop our sport with the VISION - For the Love and good of our Game”

Strategies and Techniques for augmenting the popularity of International Ice Hockey Competition

From a global perspective, the game of hockey is facing huge challenges in the coming years. In particular, we have identified five areas of the highest concern:

- I. Recruitment of young players – male and female - is a massive problem in almost every IIHF member country.

- II. Intra-league cooperation in the field of Player Development is another Challenge.

- III. Positioning of hockey in the international marketing competition of sports, especially winter sports. This is particularly true for countries where hockey is not number one, two or even less.

- IV. Maintain Integrity a public and media perception of a lack of integrity and transparency within large international associations and organizations.

We have to maintain our Integrity and set the best example! - V. Coordinated international calendar More and more games at national and international club level and the national teams as well as the KHL and NHL World Cup of Hockey requires a carefully coordinated international calendar.

The following observations highlight point V. Coordination of all hockey activities worldwide created and develop by the different stakeholders and events showed at the slide below.

For example the 2016/17 season was by far the busiest on record with the operation of the following competitions around the world under the IIHF banner:

- 2017 IIHF Championships & Qualifications 29

- 2018 OWG Men’s Qualification Tournaments: 3

- 2018 OWG Women’s Qualification Tournaments: 7

- 2017 Asian Winter Games Tournaments: 4

- 2017 IIHF Continental Cup Tournaments: 6

Total IIHF international Tournaments 49

In addition, the following games are played in different events:

- National Team Games

- Each of the Top 4 European Nations played 20 games

- Each of the Top 24 Nations played an average of 12 games

- With a total of approx.. 300 games

- NHL games (not including Playoffs) 84 games

- KHL games (not including Playoffs) 56

- Leagues in Europe with a total # of games 52-78 games

- CHL games 13 games

- Continental Cup games 9 games

- and others

Conclusion: A top player has to play more than 100 games at top level throughout on season. There is a pressing need to coordinate all of this in a common way.

Therefore, the IIHF will install a World Hockey Board with all major stakeholders: the IIHF, NHL, NHLPA, KHL, Hockey Europe and European Club Alliance to find a proper way. In addition IIHF has installed a Coordination Committee as described later in this document.

The discussion of the 10 Year International Calendar is still ongoing, with the goal of producing a long-range planning document for efficiently planning and scheduling the playing days each year for national leagues, National Teams, World Championships, Olympic Winter Games, World Cup of Hockey, Champions Hockey League and invitational tournaments.

The Role of IIHF: Besides controlling the international rulebook, processing international player transfers, and dictating and officiating guidelines, the IIHF runs numerous development programmes designed to bring hockey to a broader population. The IIHF also presides over ice hockey in the Olympic Games, and preside over the IIHF World Championships at all levels, men, women, juniors under-20, juniors under-18 and women under-18. Each season, the IIHF in collaboration with its local organising committees, runs around 25 different World Championships in the five different categories.

The IIHF is divided in 19 recommending bodies – the IIHF Committees.

One of them is the Competition and Coordination Committee, which was newly built after the Council election in Russia in May 2016. The former Competition & Inline Committee and the standalone Coordination Committee have been rebuilt to the Competition and Coordination Committee.

The new Committee was restructured to include more experienced members and ad-hoc members from different stakeholder groups, to work closely through the season to master the challenging topics that rise along the season.

The Committee not only faces the challenges of organizing and finding the best possible options for all IIHF Events and International Competitions, they also aim to find the best options in accordance with the Interests and Events from the Member National Associations, the Leagues and the Clubs.

Having a look at the different stakeholders, the Committee has quite a mission:

Furthermore, the committee focused on the following points:

- Facilitate the cooperation and discussion amongst National Associations, leagues and clubs.

- Securing the dates of International Breaks through 2023

- Specifying dates for the operation of the IIHF Championship Program events

- Establishing the dates for the operation of the World Championship through 2023

- Setting the operational dates for the Men’s Division I tournaments through 2023

- Establishing the dates of the World Junior Championship through 2023

- Setting the operational dates for the Men’s Under 18 Championship through 2023

- Addressing insurance for players participating in National Teams Breaks

- Designing and developing a meaningful National Team competition to operate during National Team Breaks

A very busy 2016/17 season - including final Olympic Qualification Tournaments, the NHL/NHLPA World Cup operated from September 17 to October 1, 2016 in Toronto, Canada with the integrated operation for NHL-contracted athletes to compete in both. Team Canada won the final by beating Team Europe with players from 7 European Countries/Associations (outside the top 4: Slovakia, Germany, Suisse, Austria, France, Norway and Slovenia - ended with the 2017 IIHF Ice Hockey World Championship in Paris, France and Cologne, Germany).

The international calendar up to 2023 is already in place as follows including

- Olympic games

- World Championships

- World Championships Div. I

- U20 World Championships

- U18 World Championships

- International Breaks

while leagues in Europe using all necessary playing dates planned around those dates

Succeeding in this mission requires

- Willingness to work together

- Listening

- Being open for all kinds of proposals

- Trying to coordinate all schedules

- Creating the best possible option in a compromise

- Start over again

A platform like the unique World Hockey Forum at Moscow will be very helpful for understanding each other. Fulfilling all the requirement our game of hockey will be growing and it will bring benefits to all of us.

Sources: IIHF, WHF, F.Reindl

Analysis of the Factors Influencing the Development of Ice Hockey

in the Global World

Sergey Altukhov, Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the Sport Management Centre of Lomonosov Moscow State University, PhD, Russia

Vladimir Ageev, Senior Consultant, PricewaterhouseCoopers Counseling, graduate student of the Faculty of Economics, Lomonosov Moscow State University. Russia

Ice Hockey in China: Russian Role in China’s Ice Hockey Market Development

1. Introduction

Ice Hockey continues to strengthen its position all around the world. Success of this unique game is primarily due to the hockey leagues financial income increase in North America, Europe and Russia, the technologies and television broadcasts quality improvement, active internet and social networks access. But high growth rates do not automatically mean the same high rates of hockey development in the world.

World ice hockey is traditionally the object of regulation of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) and occupies strong positions in the international Olympic movement. There are many reasons for pride when it comes to comparing ice hockey with other sports. But an indisputable fact is that the number of countries that make up IIHF does not increase. At present, 76 national federations are members of the IIHF. This is 35% of all possible options for membership in the international federation. There are objective reasons for this phenomenon – climatic conditions on different continents, ice rinks complex and expensive infrastructure, players specific sports equipment, power game culture, complex technical skills of hockey players, etc. But the evolutionary way of this development game dictates new approaches to solving these problems.

IIHF leaders understand the strengths and weaknesses of the world hockey project. The old product (ice hockey) released to the new Asian market strategy coincided with the decision of the International Olympic Committee to host the 2018 Olympic Games in Pyeonchang (South Korea) and the 2022 Olympic Games in Beijing (China). Asian sports market will be the focus of ice hockey experts and stakeholders attention around the world for the coming two Olympic cycles.

The ice hockey tournament final is a cherry on top of the cake and the most exciting moment for the organizers in all the Winter Olympics, since ice hockey is the only team sport in the winter games program. This dictates a special attitude to ice hockey.

2. Background and literature review

Chinese sports reform is rapidly developing and attracts scientists and experts’ attention from all over the world. A significant contribution to this process is made, first of all, by Chinese sports associations, institutes, universities, scientists and researchers. They are at the heart of it all and assess changes in real-time mode.

Rapid dynamics of Chinese sports transformation has not eliminated institutional and structural imbalance of market participants (Huo, 2011). And there is an explanation. At a time when the market economy in China was rapidly developing since the early 1990s, sports continued to remain in government-controlled planning systems. Consequently, conflicts between these state systems and professional market relations in sports seemed inevitable (Liu, Zhang & Debordes, 2017).

Studies on elite sport re-orientation in China demonstrate that elite sport in the country has transformed into different levels of commercial, state, amateur and joint structures (Liu, Sobry, Li, & Liu, 2010). All active participants adapt to changes in social and economic conditions in China, each sport develops so that to achieve the best balance between commercial and public spheres (Tang, Zou, & Zhou, 2006).

The ice hockey problems in the context of the Chinese sports community are investigated and analyzed quite rarely. Historical parallels and features of the emergence and development of ice hockey in China are presented in several articles (Guo, 1983), (Li & Feng, 2013), (Den & Guo, 2014).

The increased attention to ice hockey in Chinese and foreign researchers, is mainly due to the activity of the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) and the development of the eastern direction in the league. The political context of Russian-Chinese cooperation in the hockey program development attracts additional attention to the project. Responsible for sports policy, officials and managers must take into account in decision-making the historical experience and institutional environment of their sport (Washington, 2006). Hockey competitiveness is high enough at the international level, and in this context sports results are the main goal for everyone. However, there are times when stakeholders need to act interdependently and achieve the overall objectives (Stevens, 2017).

It should be recognized that Russia can help develop the taste for ice hockey in China on the eve of the Olympic Games and will serve as a means to improve the quality of the Chinese national team game, a team that currently occupies only the 38th place in the world and plays in the fifth division of the IIHF Ice Hockey World Championships (Lerner, 2016).

Entering a new market for a well-known product (ice hockey) will necessarily be related to the specifics of the region's economy. In the process of forming mutual relations, risks and an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the product must be taken into account. The success of a new firm entering the market depends on the product, process and organizational innovations (Twomey & Gaziulusoy, 2014). The expected challenges also have their positive sides. The sport evolution has led to formalized international norms and rules for all hockey community participants. But different cultural, political, economic and social conditions will influence the playing style of new participants (Cantelon, 2001). And it's great! National Chinese ice hockey will meet high standards of entertainment and will promote its original game model. Suffice it to recall the famous hockey game models of the Czech Republic, Sweden, Canada, Russia, Finland and other countries.

Some authors pay attention to the need for changes in hockey’s vertical management. The China Ice Hockey Association faces a violation of stereotypes. In a market environment, subversive innovations create a process in which a small company with fewer resources is able to successfully challenge existing companies (Christensen, Raynor, & McDonald, 2015). The China Ice Hockey Association is now in the status of a small (by Chinese standards) company. It is well known that football and basketball dominate the Chinese sports market and have their own long term development strategies. Ice Hockey, in the first place, faces a fierce competition in the sports services market for the Chinese with the dominance of these team sports.

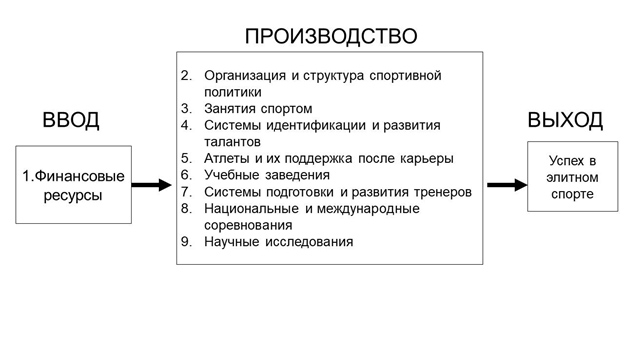

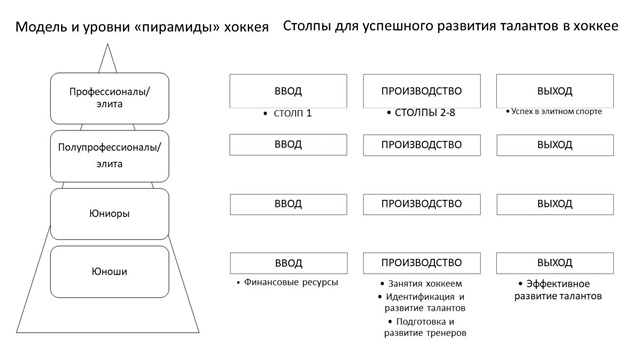

The most important task for all participants of the hockey community is the creation of modern training methods and ways of hockey player development from the initial to the professional level. The ice hockey development is built on the pyramid model, where a wide recreational base of participants feeds the system to a professional level (Emrich & Güllich, 2013). In each country, such a system works in its own way, but no matter what country-specific way of player development is chosen, the pyramidal model provides the basic building block (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, & Philippaerts, 2008). This system was mostly non-commercial in nature until recently. However, recently new forms of commercial development programs appeared in the framework of the youth hockey system in different countries of the world (Marr, 2014). And there is no conflict in this.

In the Russian research environment, works on analyzing the development strategies of joint Russian-Chinese hockey and sports projects, assessing the market and assessing the effectiveness of investment in hockey infrastructure and hockey clubs in China has not yet been fully presented. But Chinese wisdom teaches us all that the most distant path begins with the first step.

3. Case Study

Ice hockey in China. Historical aspect

China became acquainted with Canadian hockey in the early twentieth century. And the first official reports of ice hockey in China appeared in the 1920s, when a book about sports on ice was first published in Chinese. It already had a chapter on the rules of hockey matches, and it is commonly believed that ice hockey was first introduced by Western settlers in China during the colonial period (Guo, 1983).

On January 26, 1935, ice hockey first appeared as a formalized sports competition in China at the first North Chinese sports games on ice. This date is considered to be the beginning of the official ice hockey competition in China.

Ice hockey did not cause any hype in the local population. The real development of this sport began only in the mid-1950s after the establishment of the present People's Republic of China. Chairman Mao proposed the initiative "Strengthen the national spirit through the development of sports" for the rise of mass sports and citizen activism. The population of China began to be actively involved in wider state construction through the sports movement, mass participation in winter sports, which was supported by the central and local authorities of the young republic.

Leaders in the winter sports development were the north-eastern provinces of the country. The climate in this part of China is sharply continental with hot summers and cold winters. Ice hockey has sparked interest among local residents, and various hockey fan clubs began to be created one after another in universities, schools and factories. 1953 was a milestone in the development of ice hockey, when this sport was officially included in the program of the first national winter games. The number of participating teams in the first three national games has steadily increased from 5 in 1953 to 9 in 1955, and 13 in 1956 (Li & Feng, 2013). As for the foundation of the national ice hockey association, the dates vary: in different sources, 1951, 1953 and 1957 are found. It appeared as a division of the Association of Winter Sports.

The growing popularity of ice hockey in the period after World War II was the result of the Cold War outbreak and the confrontation of the Soviet Union with Western countries. Sport became a substitute for war. The USSR national ice hockey team won the first for them at the 1954 World Championship in Sweden. The Chinese Communists noted this fact for themselves and supported the Soviet initiative. In 1953 there was a hockey league, uniting amateur collectives. Then it consisted of 8 teams, and later their number ranged from 6 to 12. In 1956, China joined the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF). This was the beginning of the official exchange between the Chinese ice hockey and ice hockey in the socialist countries.

In the winter of 1956, China sent an ice hockey team to the 11th Winter Universiade in Poland, where Chinese hockey players first took part in official international competitions. The Chinese team also visited Czechoslovakia and the former East Germany after the Universiade. Despite the low result in the Games, participation in matches and visits became an impressive experience for Chinese young players, coaches and officials. China began to learn quickly from the leading hockey powers. And when the East Germany national team visited China in 1960, the Harbin hockey team from Heilongjiang Province, even managed to hold the score 0-0 after two periods (Li & Feng, 2013).

Since 1957, youth ice hockey competitions for players under the age of 18 years were held separately from adult competitions at national games in China. Although ice hockey was mainly limited to the northern part of the country for geographical reasons, these national games significantly increased the popularity of this sport among the Chinese.

Ice Hockey became a real ambassador of friendship and good neighborliness for the Soviet Union and China in 1958. For the first time in the history city of Blagoveshchensk hosted ice hockey match between China and the USSR players. The team of the Amur Region played three matches against the team of the Heilongjiang Province. The first match ended in a draw 5:5. The second and third matches were won by Blagoveshchensk hockey players 4:3 and 3:1, respectively.

The sports development in China, including ice hockey, was largely suspended in 1966 with the beginning of the 10-year Cultural Revolution – the socio-political movement initiated by Mao in China. This led to the fact that China's economic development, official state affairs and even the education system at the peak of their heyday experienced a virtual stop for a while. In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, national and local ice hockey teams, as well as many other sports, were disbanded, and sports facilities came to desolation. The national ice hockey team did not meet until 1972, when China began to establish contacts with the international community after relations with the United States became more favorable, and China's place in the United Nations was restored. In a slow pace, but the development of ice hockey in China resumed (Liu, 2017)

Since 1980, when China launched the so-called reform of open politics, led by Deng Xiaoping, the development of sports, including ice hockey, has entered a new and fast-growing era. In 1981, the Chinese Ice Hockey Association was officially established in Beijing. Since the early 1980s, the Hockey League has become very popular; competitions have become increasingly tense and entertaining, especially at the final stages of each season (Li & Feng, 2013). During its rise in the 1980s, 20 professional ice hockey teams were organized, about 1 million people regularly practiced ice sports, among which 100,000 people played ice hockey (Li & Feng, 2013). China also won the men's hockey tournament gold medals of at 1986 and 1990 Winter Asian Games. (Den & Guo, 2014).

Since the mid-1990s, the popularity of ice hockey started to decline both at the level of sport of higher achievements, and at the mass level. The state stopped financing professional clubs, many teams were dissolved, and the number of professional teams dropped from 20 clubs in the 1980s to 3 clubs in 2010. At the same time, all three teams were from Heilongjiang Province, which turned the national ice hockey championship into a provincial competition (Li & Feng, 2013). Amateur ice hockey clubs were also disbanded one by one, and the Chinese national team lost its leading position in Asia. Leading state-owned companies and industrial enterprises of China to stop financing ice hockey. But since the 1990s, this situation began to change. The impetus to change was the transition of the state from a planned economy to a market economy.

Chinese Sports Reform

In the course of implementing the policy of openness and reform proclaimed by the new communist leaders led by Deng Xiaoping, the transition from a planned economy to a market economy without a collapsing liberalization policy was made. Thanks to such a strategy, China managed to avoid the economic recession, the growth of inflation and many other negative phenomena. The agrarian country has received a powerful push in development, thanks to property reform, price liberalization, and foreign trade reform. Reforms of the social sphere at that historical stage were not considered. The state attention to the sports industry was manifested much later, when China got the right to host the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

It was the 2008 Olympic Games that became the impetus for the formation of a new main task in the development of China's sports industry – the transformation of China from a strong sports country into a mighty sports power.

On October 20, 2014, the State Council, the Cabinet of Ministers of China approved the "Program for accelerating the development of the sports industry and encouraging the consumption of sports", calling on the General Administration of Sports of China, the supreme sports body, to weaken tight control and allow more organizations and private businesses to enter the market where state-owned companies dominated for a long time. In accordance with the plan of the national sports administration and its branches, the administrative centers will give up their organization and supervision rights for commercial and mass sports events.

"It is necessary to completely unload the enterprises of the industry for the development of the viability of all kinds of sports resources," – says a statement published by the State Council. In fact, it is believed that this centralized management system in itself has become one of the main obstacles that must be reversed and reformed to release the huge market potential of the sports industry in China (Liu, 2008).

At the 5th Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China of the 18th convocation in 2015, the "Proposals of the CPC Central Committee for the Development of the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development of China" were adopted. In the section on sports development in the 13th Five-Year Plan, it is noted that by 2020, China's total sports industry will exceed 3 trillion yuan ($ 500 billion). The average annual rate of growth in this sector can exceed the rate of economic growth over a similar period of time, the share of the sports industry in the country's GDP will reach 1% by 2020 (compare 0.6% in 2012), and the share of the value added of the sports industry services sector will exceed 30%. The volume of so-called sports consumption in proportion to the average disposable income of residents will be more than 2.5%. The sports industry will cost more than 5 trillion yuan ($ 815 billion) by 2025, with an annual gross profit of 1.7 trillion yuan or about 1.2-1.5% of national GDP by 2025.

One of the key tasks of this plan will be the organization of the 2022 Olympic Winter Games in Beijing. Therefore, the city-organizer Beijing became a "strong point" in the popularization of winter sports in China. In the winter of 2017, a series of events and competitions was held in Beijing under the slogan "We will meet the Winter Olympics with popular mass sports, the implementation of a snow and ice dream". In addition, primary and secondary schools in the capital have introduced lessons on winter sports to stimulate the younger generation to engage in these sports outside the educational institutions.

Russia and China: Ice Hockey partnership

Ice hockey deserves a special attention in the program of sports reforms. The concentration of resources and the change in the goal setting in the Ice hockey infrastructure and sports reserve preparation allowed the Chinese leaders to form new strategies for Ice hockey development in the overall program of China's sports reform. Beijing status "a capital" of a 2022 Winter Olympic Games assumes Chinese national ice hockey team mandatory participation, team that currently occupies only 38th place in the world ranking. The prospect of creating such a competitive Chinese team by 2022 forced the Chinese authorities to seriously address this problem.

The Chinese played into the hands of the fact that another country is experiencing similar difficulties. This is South Korea. The Olympic Games in this country will be held in February 2018. Currently, the Chinese national ice hockey team is significantly inferior in the team rating to the South Korean team. But the Korean transformation in ice hockey began much earlier – in 2010. All Olympic Games organizers understand that the host country hockey team participates in the Olympic tournament without qualification and must be adequately presented to the public and home audience. To solve this problem Koreans turned to the program of hockey players’ naturalization and Korea citizenship assignment to players from other countries. This proposal helped in a short period to create a professional ice hockey team and solve the problem of entering the IIHF World Championship Division I. Today, all Koreans are optimistic about the ice hockey Olympic prospects and hope for a successful performance of their team.

Chinese sports leaders decided to go the other way. For the Chinese national ice hockey team preparation, they decided to take advantage of Russia's experience. The political rapprochement of the two neighboring states, cooperation in the sphere of economy, culture, education, and sports became a reliable basis for the creation of a joint program for the development of ice hockey in China according to Russian patterns. This decision was dictated by the logic and expediency of developing a new partnership between the two neighboring countries.

Russia, and earlier the Soviet Union, has a rich victorious experience in international competitions, infrastructure preparation, sports reserve education and ice hockey tournaments of various levels. In 2016 Russia’s ice hockey infrastructure included 583 indoor ice rinks. 528,000 Russian citizens regularly practice hockey, 98,000 children are trained in children's sports schools (kremlin.ru). Chinese hockey statistics looked much more modest. About 20,000 people, of whom more than 1,200 are registered as professional hockey players are involved. Ice Hockey infrastructure is about 100 ice rinks, of which 48 are in closed premises. In addition, in China, 98 ice hockey referees are registered.

After the joyful announcement about the 2022 Winter Olympic Games organization, China announced an ambitious plan to attract 300 million people to winter sports in the next six years (Sun, 2016). The Russian side offered its vision on the implementation of this task.

On June 25, 2016, within the framework of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to China, an agreement on the entry of the Kunlun Red Star hockey club into the Continental Hockey League was signed. The treaty was signed in the presence of Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jingping, who thus once again demonstrated the existence of a "special level of relations" of the countries. Thus, in China the first professional ice hockey club in the KHL appeared, the formation of the domestic ice hockey market, the education of ice hockey and corporate culture, Ice hockey fashion in China has begun. Despite the costs of growth, the first partnership experience can be considered positive.

Traditionally in China, the phrase “Kunlun” hit the big time. Kunlun Mountain is an analogue of the ancient Greek Olympus, the habitat of the gods. Kunlun Shan in Chinese means "Moon Mountains". This is the name of one of the largest mountain systems in the country. The first Chinese scientific station in Antarctica also received the name "Kunlun". Now in Chinese history there is also a hockey club "Kunlun Red Star". In the first season in the KHL, the Chinese club got into the playoffs, and by 2021 the club's strategy provides the refusal from the foreign players in the team.

Promotion of youth ice hockey in Beijing shows excellent progress over the past two years. More than ten thousand students from sixty schools learned about this game and began regular training. This was reported by the Beijing Hockey Association (BHA). Under the auspices of the BHA, 116 club teams were registered, consisting of 2,000 children registered to participate in the 2015/16 season in the Hockey League of Beijing. This is significantly different from the first season of this league in 2008, when less than 20 official players were presented and only four teams were represented. Preparation of the sports reserve will also be undertaken by North American partners. Professional women's team will compete in the Canadian League – CWHL. Young men and girls from junior Chinese teams under 18 will be trained in Canada and Boston.

A significant step in the ice hockey partnership development of Russia and China is the resurgence of match meetings on the Amur River between Russian and Chinese hockey players. In the history of these countries there was once a memorable match – in 1958 a meeting was held in Blagoveshchensk between a team from the Amur Region and a team from Heilongjiang Province. Then it was played in three matches. January 14, 2017 a new meeting of Russian and Chinese hockey players on the border of two countries. This time, two matches were played and Russian hockey players won them. Organizers plan to make such matches annual; adults and children's teams will be able to take part in them.

The dynamics of positive ice hockey relations of Russian and Chinese partners led to a new step. The parties suppose that the new Asian Hockey League, in which hockey clubs of Russia, China, Japan, Korea and Kazakhstan will be able to participate, should become the long-term goal of cooperation. In the meantime, the new "Silk Road Cup" will be the new ice hockey ground. This is stated in the Memorandum signed on July 4, 2017 by Russia Ice Hockey Federation, China Ice Hockey Association and Center for International Cultural Relations of China in Moscow.

"Silk Road Cup" is planned to be started from the 2018/19 season with all teams competing in VHL Hockey League (both from Russia and Kazakhstan) included automatically and other 5-6 hockey teams from China to join. It is estimated that a total quantity of competing teams will be around 30. Starting from season 2019/2020 4-6 new teams from Silk Road countries (Korea and Japan) will be added, and so two conferences could be formed – European and Asian – which will allow reducing the travel expenses. The new tournament can replace national championships, and national titles can be rewarded to the most successful teams from their countries on the basis of the final standings.

RIHF and CIHA can build a brand – new ice hockey competition on the basis of the existing legal entity epovered by the Russian low – VHL – non profit organization. Board of Directors will comprise 51% CIHA members, 49% RIHF members.

The Russian law does not allow to create leagues as international organizations, which could be considered All-Russian competitions. In order for the Russian clubs to keep funding from the local budget, their participation should be approved by Russian Government and the Ministry of Sports of Russia.

RIHF suggests to found Silk Road Cup on the following principles:

- NPO VHL jointly with the RIHF organizes the VHL competition for the Silk Road Cup.

- RIHF will be in charge of the officiating, schedule and regulations development, contracts with the clubs, clubs application process, statistics.

- RIHF delegates all TV and marketing rights to the NPO VHL for the compensation covering RIHF expenses for its services and travel expenses for Russian clubs.

- Assessment of the compensation for the RIHF services – sport management plus officiating – 3.5 M USD a year (not including travel expenses)

- No admission fees of the clubs – this money should be invested in infrastructure development (boards, lighting, ice surface, etc)

Sport principles of Silk Road Cup first season:

- The Silk Road Cup will start from the 2018/19 season

- All the VHL clubs will be included automatically

- 5 or 6 Chinese clubs to join

- Est. 30 clubs will start from the first season

- Clubs of each country could be counted as separate regional Championship points, national titles should be rewarded

Sport principle of the second season:

- 4 or 6 extra teams of Silk Road countries (Korea, Japan) will be added

- 2 conference could be formed (European and Asian), which will allow to reduce the travel expenses

Marketing.

New joint product by RIHF and CIHA should aim to become the third best professional Ice Hockey league. There for there is a necessity that is substantial investments in the participating clubs and stadiums infrastructure:

- Brand identity and promo campaign launch – redesign, ad campaign on TV, outdoor, digital promo.

- New standards of infrastructure for the clubs and stadiums (lightings, boards, etc) for the TV production and marketing needs

- Production of the matches on the High quality, TV broadcasts of the best games, daily league content production for dedicated shows and highlights on TV and internet.

- Game-center and live statistics application for fun.

- Web-site, application for smartphones and Smart-TV, social network program development, media partners – web-sites, blogs, PR support of the partner media of the RIHF.

Business extension.

- NPO VHL will focused on Chinese market and regional sponsors.

- A series Silk Road events will be integrated in the launch and promo campaign (Culture, Business, Science events).

- International players are welcome to play in the league.

- Generate revenues from fans and sponsors outside the games.

- Target break-even – year 2.

The signed memorandum also envisages that the Ice hockey clubs of Harbin and Jilin will be able to compete in the VHL Hockey League starting from the 2017 season. In 2018, three more Chinese clubs will appear in this league, and by 2022, 10 clubs from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Hong Kong will represent China in the VHL Hockey League.

Such a development strategy should envisage mutual integration and market mechanisms for promoting ice hockey in new regions. Optimistic forecasts suggest that not only Russian and Chinese companies will sponsor this project. Involvement of Japanese, Korean, American, Canadian partnerships is a global task for the hockey market of China in the near future.

For the sake of what all these unprecedented efforts to create a new hockey market in China are made? The answer will not be original. Resources and influence. The expansion of the Continental Hockey League to the East in the future can bring the league a new audience and growing revenues from the television rights realization at a new market. In the event that only 1% of China's population is interested in ice hockey, the target audience of consumers will be about 15 million people, which is more than the total television audience of the final matches of the Gagarin Cup and Stanley Cup put together. This can already be considered a market control. In addition, a new hockey culture will help the Chinese to shape new relations with partners and a new policy. Ice Hockey is facing a new challenge. In terms of systemic changes in the global geopolitics such prospects are worth fighting for.

REFERENCES

- Cantelon, H. (2001). Revisiting the introduction of ice hockey into the former Soviet Union. In C. Howell (Ed.), Putting it on Ice: Volume II: Internationalizing Canada’s Game, 29-38. Gorsebrook Research Institute: Halifax, NS.

- Christensen, C., Raynor, M., & McDonald, R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 8, 2015 from https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation.

- Cunningham, G. (2014). Interdependence, mutuality, and collective action in sport. Journal of Sport Management, 28, 1-7.

- Emrich, E. & Güllich, A. (2013). Considering long term sustainability in the development of world class success. European Journal of Sport Science, 14, S383-S397

- Huo, D. (2011). The innovation of sports institution and the choice of its path in our country in transition. Journal of Shandong Institute of Physical Education and Sports, 1. Retrieved on December 4, 2016 from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-TYYK201101004. htm.

- Liu, X., Sobry, C., Li, J. & Liu, J. (2010). “Joint decentralization”: some reflections on the organization structure of high-performance sports events in China. Kinesiology, 42, 132-141.

- Marr, L. (2014). Amateur hockey is slick business. The Hamilton Spectator. Retrieved on December 1, 2016 from http://www.hamiltonbusiness.com/dir/2014/11/amateur-hockey-is-a-slick-business/.

- Tang, J., Zou, W., & Zhou, H. (2006). Sport system reform and the market mechanism of China. Journal of Shandong Institute of Physical Education and Sports, 6. Retrieved on December 4, 2016 from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Journal_en/H-H134-TIRE-2006-05.htm.

- Twomey, T. & Gaziulusoy, I. (2014). Review of system innovation and transitions theories: concepts and frameworks for understanding and enabling transitions to a low carbon built environment. Visions and Pathways Project.

- Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., Williams, M., & Philppaerts, R. (2008). Talent identification and development programmes: current models and future directions. Sport Medicine, 38, 9, 703-714.

- Washington, M. & Ventresca, M. (2008). Institutional contradictions and struggles in the formation of U.S. Collegiate Basketball, 1880-1938. Journal of Sport Management, 22, 30-49.

Young Hoon Kim, Chair in the Department of Hospitality and Tourism Management at the University of North Texas, USA, PhD

Is Ice Hockey on the Right Track in the Republic of Korea?

2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics and Next

Thanks to the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics in Korea, ice hockey in South Korea is now emerging into the new stage: New Era – “Post-Olympics.” Addition to its promotional strategies in Korea, ice hockey became the key mediator for a historic Olympic run by the unified Korean women’s ice hockey team. The NBC News described the unified team’s game against Switzerland on February 10, 2018, “They may have lost in their debut game at the Winter Olympics on Saturday night, but the first-ever joint Korean women's ice hockey team easily won the crowd” (Ortiz and Abdelkader 2018). Now, ice hockey is not only for fans in the Korean peninsula but also, for both governments to open the table for discussion.

Mega sport events (e.g., 2002 Korea-Japan World cup) always play a major role for a hosting country: i.e., tourism, culture, economy, and arts – even for politics. It is also believed that major hockey leagues, such as KHL in Europe and Asia are trying to make steps to create its own story in Korea. The current proposed chapter will be attempting to answer the following questions: 1) What are the current issues? 2) Journey for 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics 3) 2016 -17 Season Achievements 4) Strategic Plan of KIHA (Korean Ice Hockey Association) 5) Current Promotional Strategy and 6) New Era – “Post-2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics. In addition, this chapter attempts to address challenges for Korean ice hockey by investigating any issues in Korea.

The Contents

- Current issues

- Journey for 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

- 2016 -17 Season Achievements

- Strategic Plan of KIHA (Korean Ice Hockey Association)

- Promotional Strategy after the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

- Conclusion and suggestions

Current Issues

Firstly, major challenges and issues of ice hockey in Korea can be explained by its administration system and governmental support. Although ice hockey is now one of the popular winter sports, the financial support by government is minimal. According to a personal interview with Jingmin Kim, the marketing and promotion director of KIHA (2017), “Korean National Ice Hockey Team has had a difficulty in attending international tournament because of its limited budget and financial support. Thus, the new appointment of Mr. Chung, the President to KIHA was one big moment for the Korean Ice Hockey Team.” Secondly, the restricted frequency of broadcasting and televising was one the major problems of marketing. Internal games was never televised live through Korea Broadcasting until 2013. In March 2013, Mr. Jungmin Kim, the former sport journalist was hired to increase the media attention and appearance. The popular portal website (i.e., naver.com) was utilized for live broadcasting of 2017 World Championship games. Thirdly, costs. As one of the most expensive sports: equipment, gear, and place to play which is still one big challenge: the ice arena. Although we had many new arenas built for the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics, it is still in short.

Journey for 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

It was not an easy journey for the Korea National Ice Hockey Team to advance to the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics. The steps were:

- 2011: PyeongChang named as the host city for 2018 Winter Olympics

- 2012: Recommendation by Rene Fasel, the President of IIHF: the World Rank: 18th was suggested to be eligible for qualification

- 2013: Mr. Chung (CEO of Halla Group) was appointed as the President of KIHA – with two important objectives in the Strategic Plan: Going up in the World rank and qualification. Ranked 5th in the Division I Group A – 2 Wins and 3 Losses

- 2014: 5 Losses and down to the Division I Group B

- 2014 events:

- In August, Jim Paek was hired as a Head Coach of the S. Korea National Team.

- In September, Mr. Paek presented “Strategic Plan for South Korea Men’s National Team” at the IIHF Semi Annual congress; finally, both men and women teams was qualified for 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics.

One of the biggest turning points for the Korean National Team was 1) Mr. Chung’s (the President of KIHA: Korea Ice Hockey Association) appointment and 2) Mr. Paek’s joining as a head coach in 2014. Mr. Chung addressed his vision in his introduction, “it is not long enough to improve all areas for Korean Ice Hockey National Team but I believe it is not too close as we think. Let’s make it better day by day. There is no doubt that we can see our New Horizon on Ice at the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics” (KIHA, 2018). In addition, Mr. Paek states, “It’d be great to say, ‘Yeah, we’d like to move up into the top 16 in the world first, and hopefully make the Olympics.’ But if it’s not the Olympics, so be it. What’s important is that we’re competitive and improve every day” in his interview with New York Times (Klein, 2014).

2016-17 Season Achievements

IIHF (International Ice Hockey Federation)

- Men: 2nd Place Division I Group A and World Championship

- Women: Champion Division II Group A and Advanced to Division I Group B

2017 Sapporo Asian Winter Olympics

- Men: Silver Medal

- Women: 4th Place

IIHF World Ranking 2017

- Men: 21st (32nd in 2007)

- Women: 22nd Place (26th in 2007)

The results of 2016-2017 season was not as successful as expected but it has clearly proved that both Korean National Teams are now among the world class teams in the Division I. It was not exactly as Rene Fasel, the President of IIHF recommended but its rank was high enough to compete in the world-class tournament at the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics.

Strategic Plan of KIHA (Korean Ice Hockey Association)

- Vision Statement: “One-Body” – One movement under one vision and mission to create new ice hockey history.

- Mission Statement: To become an ice hockey leader and create new market in Asia through the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics by working with IIHF and KIHA.

Three Major Goals:

- Based on Success of 2016-17 Season

- Make a big step at the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

- Promotion and advance to the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics

With three major goals, both women and men teams have their own strategic plan. Men’s team has two major plans: 1) international off-season/field training by having games and competing against world top-ranked teams and 2) cooperation with business teams. Especially, they reduced games in Asia League (AL) from 48 to 28 to spend more time in training and preparing for the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics. On the other hand, women’s team has four bold goals: 1) competition with world ranked teams, 2) international off-season/field training, 3) hosting 2017 women’s ice hockey league, and 4) develop a strong foundation for growth sustainability. However, one of the most achievements was the unified team. The game results was not successful but its contribution to the Olympics’ spirit is more than any medals.

Promotional Strategy after the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics

There is no question that the popularity of ice hockey will grow after the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics but there are many ways how to succeed in and to become more popular among many winter sports. Building a new bridge with NHL or having games with world top ranked teams can be the other opportunity. Summer camps and training programs with juniors and charity events with Korean National Team, NHL, and top ice hockey legend players will be providing us with a great opportunity in promoting. However, the most important thing is that maintaining the quality of team playing and world rank. Then, star player marketing which has been a keyword for Korean sports. KIHA’s promotional plans are followed:

- Qualify for 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics

- Maintain world rank and stay in World Championship League

- Establish an U-18 Women’s National Team

- Build Ice Hockey-Rinks and utilize the Kangneung Ice Hockey Center

- Support youth/junior programs

- Leadership/management program for Ice Hockey

Conclusion and Suggestions

A CNN News article says, “As he made his way to the stadium with his family, his young son waving the now familiar flag of a united Korean peninsula, Jung Jin-suk, from Suwon in the north west, said he hoped the unified team could help improve the South's understanding of the North” (Lewis, 2018)

"Many people are excited," he told CNN Sport. "Maybe 99% of the people will be happy, but 1% aren't because they have bad memory about the Korean War. After this event, I hope that many South Korean people can understand North Korea better."

In conclusion, the question can be addressed, “can success of the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics lead to the place where we want to go?” Maybe, the place is not only for political perspective but also for the ice hockey business in Korea. According to Wang (2011), “Olympic Games has a good public image and a unique social appeal” (p., 383). The die has been thrown for all stakeholders but we are not sure who will take the die for next turn.

References

Ortiz, E., & Abdelkader, R. (2018, February 10). Unified Korean women’s ice hockey team debuts at Olympics to heartfelt cheers. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/winter-olympics-2018/unified-korean-women-s-ice-hockey-team-debuts-olympics-heartfelt-n846636

Chung, M. (2013). The introduction of KIHA President. Korea Ice Hockey Association. Retrieved January 3, 2018, from http://www.kiha.or.kr/kiha/%ED%9A%8C%EC%9E%A5-%EC%9D%B8%EC%82%AC%EB%A7%90/

Klein, J. Z. (2014, August 14). Jim Paek Is Building South Korean Hockey Program. Retrieved April 14, 2017, from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/sports/hockey/jim-paek-is-building-south-korean-hockey-program.html?_r=0

Kim, J. (2017, November 11). Personal Interview.

Lewis, A. (2018, February 12). Unified Korean ice hockey team proves that 'winning isn’t everything. CNN news. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/10/sport/south-and-north-korea-ice-hockey-intl/index.html

Wang, H. (2011). Analysis of modern sports marketing of post-Olympic era. Journal of Human Sport & Exercise, 6(2), 378 – 384.

Jyri Backman, Master of Law and Sports Management, University of Malmö, Sweden.

Ice Hockey Organization and Innovation in Sweden and Finland

Introduction

From a commercial point of view, the 1990s was a decade that changed Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey (in the following article I refer to men’s elite ice hockey due to the fact that women’s elite ice hockey lives under different circumstances). During the 90s television, Bosman case, sponsorship, increased (media) exposure and corporation – in addition to traditional public revenue – was a catalyst for increased commercialization. This decade can be seen as the period when Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey made a “commercial brake (run) away” to other national sports. The aim of this article is to address some key issues in the professionalization and commercialization – and especially corporation – of Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey. In the following article I will give – in a Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey perspective – an introduction to the organization of sport and ice hockey, a brief overview of the financial status and development of corporation. After this I will sum-up some of the key factors in the process of professionalization and commercialization in Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey. This essay is an enlargement of my presentation at World Hockey Forum in Moscow, December 14–15 2017.

The organization of sport and ice hockey in Sweden and Finland

Sweden and Finland are countries with strong historical, societal, religious and governmental ties with a similar tradition of organizing sport (amateurism, non-profit, fostering, youth, promotion and relegation etc.), and members of the European Union (EU) since 1995 (Backman, Jyri, 2012).

Sweden

Swedish sport and elite ice hockey is organized according to the European Model of Sport with the Swedish Ice Hockey Federation as the governing body for all Swedish ice hockey. The Swedish Ice Hockey Federation is a member of the Swedish Sport Confederation, established 1903. The Swedish Sport Confederation consists totally of 71 sport federations, approximately 20,000 sport clubs and 3 million persons as members. The Swedish Sport Confederation and sport federations also consist of regional sports federations that act as administrative bodies for the Swedish Sport Confederation and sport federations. The Swedish sports model is further characterized by the fact that amateur sports, children´s and youth sports are combined with commercial and professional sports in the same organization (Swedish Sport Confederation, Annual Report 2016; Backman, Jyri, 2012).

The dominant view in Swedish ice hockey literature is that American film director Raoul Le Mat introduced ice hockey in Sweden in connection with Sweden´s participation in the Antwerp Olympics in 1920. According to historian Tobias Stark, however, this is a simplified explanation. Although Le Mat had an important role, the Swedish Football Association´s secretary Anton Johansson and the Olympic Committee´s treasurer Sven Hermelin should be highlighted as the main representatives of the initiative. During this time, there was no ice hockey organization in today´s opinion, even though the Swedish Football Association became a member of the International Ice Hockey Federation (LIHG/IIHF) in 1912. As ice hockey grew in popularity and expansion, the idea of a separation from the football was awakened. The final separation between football and ice hockey took place in 1922: The Swedish Ice Hockey Federation was founded (Stark, Tobias, 2010). The Swedish Ice Hockey Federation has since been the governing body for all Swedish ice hockey.

Characteristic for Swedish ice hockey is that the premier league (Elitserien/since 2013 SHL) is on sporting grounds open, i.e. promotion and relegation. Well established is also the principle of utility-maximization, in which economic profit should be reinvested in sporting activities, which is confirmed by the fact that non-profit sport clubs are tax-advantaged (Backman, Jyri, 2012; Malmsten, Krister and Pallin, Christer, 2005; Swedish Sport Confederation, Annual Report 2016).

Finland

Finnish sport is, on the other hand, by historical reasons fragmented even though harmonization work is ongoing. In Finland, there were several self-governing sports organizations in the years 1906-1993: Finnish Sport Confederation (1906-1993), Workers Sports Federation in Finland (established 1919 and still operational), Finland’s Swedish Central Sport Federation (established 1945 and still operational), Finnish Football Federation (established 1907 and still operational), Finnish Olympic Committee (established 1907 and still operational) and Finland’s Workers Central Sport Federation (1959-1979). In order to create an even more unified sports organization, Finland´s Sports, Young Finland, Finnish Sport Confederation and Finland´s Olympic Committee formed in summer of 2012 Valo (Finland´s National Sport Organization). By forming an umbrella organization, the four founders wanted to develop Finnish sports. In connection with the start of the formal activities of Valo on 1 January 2013, Finnish Sport Confederation was dissolved. Sport federations and other sport organizations were invited to join Valo in the spring of 2013. The major sport federations (such as the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation and the Finnish Football Association) and several other Swedish-language sport federations initially waited to join in the fall of 2014. Valo was active between 2013-2016 for on January 1, 2017 they were to be replaced by the Finnish Olympic Committee as umbrella organization for all Finnish sports as a result after the merger of Valo and the Finnish Olympic Committee. Although the Finnish Olympic Committee since January 1, 2017 is the umbrella organization for Finnish sport, the sport federations and other member organizations have very high autonomy and self-governing in matters relating to their own activities. In addition to the wishes of the founders with the new umbrella organization, the merger was driven by economic reasons. Since Finnish sports are largely financed by government funds through the Ministry of Education and Culture, the use of state grants is enhanced by an umbrella organization. Note that Finnish sports overall, ice hockey is the only exception, lacks major sponsors in addition to the state grants, which come from, among other things, the gaming company Veikkaus. In other words, the posture of the Finnish government can be seen as an approach to the pyramid structure of the European sport model. At the same time, there is a less well-established pyramid structure in Finnish sport since individuals become members of sport associations, which in turn are members of sport federations, such as the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation (Lämsä, Jari, 2017; Lämsä, Jari, 2017b; Backman, Jyri, 2012). In the review by the researcher Jari Lämsä, Finnish sports organization in 2015 comprises of approximately 1.1 million members as well as 9,000 sports associations and organizations. Regionally there were 15 sport organizations, 14 sport institutes and several other regional sport organizations. At the national level there were 70 sport federations and 38 other national sport organizations (of which 8 Swedish-language sport clubs) (Lämsä, Jari, 2017b). Non-profit sport clubs are like Swedish nonprofit sport clubs tax-favored (Finnish Tax Act, 30.12.1992/1535, 3 chapter 22–23 §§). In this context Finnish ice hockey is situated.

There are some different indications when ice hockey came to Finland. One states that ice hockey was played in the Finnish capital Helsinki for the first time in 1899. Another is that it was Leonard Borgström who tried to introduce ice hockey in Finland in the late 19th century. There is also information that it was Yrjö Salminen who introduced ice hockey in Finland in the late 1920s after learning the game in Canada. Regardless, the start of the new ice hockey sport in Finland was not entirely hassle free. Interwar times were a difficult time in Finland, at least not financially. The people had other things to consider than to play ice hockey (Otila, Jyrki, 1989; Mesikämmen, Jani, 2001; Kuperman, Igor, Szemberg, Szymon and Podnieks, Andrew, 2007). Unlike Sweden, Finland did not participate in the Antwerp Olympics in 1920. The reason why Finland refused participation was that Finland felt that the foreign rules and training difficulties made participation impossible (Stark, Tobias, 2010).

One major step in the formalization of the Finnish ice hockey was that the game was organized in 1927 under the Finnish Skating Federation, which also released the first game rules, based on the IIHF rules for ice hockey in Finland. Finland was taken up by the Finnish Skating Federation as a member of the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1928 (Honkavaara, Aarne, 1978). As a result, ice hockey started to get a foothold and the organized ice hockey in Finland began to take shape. At the sporting level, the first historic international match between Sweden and Finland was played in Helsinki on January 29, 1928, which ended with a clear Swedish victory by 8-1 (Stark, Janne [ed.], 1997). At the organizational level, a major step was taken in 1929 when the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation was formed (Otila, Jyrki, 1989; Mennander, Ari and Mennander, Pasi, 2003). Since then, the Ice Hockey Federation has been a member of the International Ice Hockey Federation and the Finnish Olympic Committee. In connection with ice hockey´s growth in Finland, the sport started to concentrate on the larger cities (Mesikämmen, Jani, 2001). In total, it can be noted that ice hockey was established approximately ten years later in Finland than in Sweden. The Olympic debut in 1952, which was 32 years later than Sweden´s Olympic debut, ended in Oslo with seventh place.

The organizational body for the Finnish premier league SM-liiga is SM-liiga Ltd. who is an autonomous organization from the Finnish Ice Hockey Federation, even though there is an agreement between the parties. The Finnish elite league SM-liiga is a closed sport league (i.e. no promotion or relegation), during 2000/2001–2008/2009 and 2013/2014–currently (Backman, Jyri, 2012).

Financial status in Swedish respective Finnish ice hockey premier league in season 2015/2016

From a financial point of view the, the Swedish SHL clubs – despite the fact that SHL is “open” – had a turnover of approximately SEK 1.7 billion (SEK 1 688 million) a year. The SM-liiga clubs had, according to the Finnish business magazine Kauppalehti a turnover in 2015/2016 of about 92 million euros, note: Jokerit from Helsinki is not included in these numbers – the club plays in KHL since the 2014/2015 season (KPMG, 2015; EY, 2016; Kauppalehti, 2016-09-16). In relation to Sweden´s respective Finland´s GDP in 2015, the turnover was almost similar. Note: Sweden´s GDP is more than double the size of Finland, in 2015, Sweden´s GDP was SEK 4.181 billion, while Finland´s GDP was EUR 209 billion, corresponding to SEK 1.923 billion (GDP from Statistics Finland and Statistics Sweden).

Corporation in Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey – a historical background with current status

The elite ice hockey clubs should establish their own (league) now and then we will continue to make coffee and sell bingo lottery tickets in our amateur clubs as nothing - or maybe something little - has happened.

This quote from a Swedish evening newspaper Expressen (1997-10-21, p. 37), arises several interesting questions, problems and tensions.

During the second half of the 90s, there were several clubs who realized what opportunities corporation and a stock exchange introduction could lead to. The Swedish clubs that went in front were Djurgårdens IF from Stockholm and Leksands IF from the landscape of Dalarna. Stock experts considered that Djurgården Hockey Ltd.´s (Plc.) stock market introduction in 1997 was only the beginning, and more and more elite ice hockey clubs would follow Djurgården Hockey Ltd. on the stock exchange. The chairman of Leksands IF Björn Doverskog clearly stated in Expressen in 1997 that the only thing that was counted for Leksand IF was corporation and stock exchange (Expressen, 1997-04-17).

It was at the annual meeting in 1997 that Djurgården´s IF Ice Hockey Club presented the proposal to list Djurgården Hockey Ltd. on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. Before that, Djurgården had received – from the Swedish Ice Hockey Federation – a principle decision to operate as a limited company. Introduction date was set to October 20, 1997, and introduction stock price was SEK 75. The interest was so big that it was over-subscribed (reported interest greater than issued shares) and the calculation was SEK 45 million. Through corporation Djurgårdens IF Ice Hockey Club had converted its debts of SEK 7.5 million to a substantial surplus. While the introduction date was approaching, critical votes in sports Sweden began to be heard, and among the main critics there was the chairman of the football federation. In this process, the requirement for exclusion of Djurgården´s IF Ice Hockey club from the Swedish premier league (Elitserien/since 2013 SHL) was expressed. In an attempt to solve the problem, Djurgården´s IF Ice Hockey Club changed its agreement with Djurgården Hockey Ltd, but found no mercy at the Swedish Sport Confederations board. As a result, Djurgården Hockey Ltd. abandoned stock introduction. Djurgården Hockey Ltd. was forced to pay back all of the SEK 45 million plus interest corresponding to SEK 6 million, to shareholders (Expressen, 1997-04-12, 1997-04-17, 1997-06-05, 1997-09-04–1997-09-26, 1997-10-11–1997-10-23). As a consequence, of the occasionally powerful corporate debate, that followed, the Swedish Sport Confederation took the historic decision – in May 1999 – to allow sport Ltd./Plc. (corporation). However: restriction that a non-profit sport club must have share majority (voting) in the sport Ltd./Plc. (company), so-called 51-percent rule (Backman, Jyri 2012).

In the table below, part of corporation in the Swedish premier league (SHL) season 2017/2018 will be displayed. The table has the purpose of showing which of the SHL-clubs performing their activities as sports limited companies and those of SHL-clubs who owns whole/and/or part Ltd.´s and holding company´s. The commercial purpose of a holding company is to be the parent company of (a) Ltd.´s. The reader should keep in mind that ownership can change and vary.

|

Mother company: Non-profit sports club (not translated) |

Sport Ltd. 51-percent rule (translated) |

Whole/and/or part owned Ltd.´s and holding company´s |

|

Brynäs IF Ishockey-förening (Gävle) |

– |

X

|

|

Djurgården IF Ishockey-förening (Stockholm) |

X Djurgården Hockey Ltd. (Public limited company, Plc.) |

X |

|

Frölunda Hockey Club (Gothenburg) |

– |

X |

|

Färjestad Bollklubb (Karlstad) |

– |

X |

|

HV71 (Jönköping) |

– |

X |

|

Karlskrona Hockey Club |

X Karlskrona Hockey Club Sport Ltd. |

X Holding company: Karlskrona Hockey Holding Ltd. |

|

Linköping Hockey Club |

X Linköping Hockey Club Ltd. |

X Holding company: Linköping Hockey Club Ltd. |

|

Luleå Hockeyförening |

– |

X |

|

Mora IK |

– |

X |

|

IF Malmö Redhawks |

X Malmö Redhawks Ice Hockey Ltd. |

X Holding company: Malmö Redhawks Holding Ltd. |

|

Rögle Bandyklubb (Ängelholm) |

– |

X |

|

Skellefteå AIK Hockey |

– |

X |

|

Växjö Lakers Hockey, VLH |

X Växjö Lakers Idrott Ltd. |

X Holding company: Sport Development Sweden Ltd. |

|

Örebro Hockey Klubb |

X Örebro Elite Hockey Ltd. |

X Holding company: Örebro Hockey Holding Ltd. |

Corporation in the Swedish premier league (SHL) season 2017/2018, (X = yes, - = no).

As my compilation shows corporation is well established in Swedish elite ice hockey, even though several clubs operate as non-profit sport clubs meanwhile 6 clubs have transformed into Sport Ltd.’s.

When the Finnish premier league SM-liiga was established in 1975, the representatives of Finnish elite ice hockey discussed the need for all associations to be transformed into limited companies, all in order to increase commercialization and professionalization. However, the proposal would prove too big to take at this time (Backman, Jyri, 2012). The first club to become a Ltd. in SM-liiga was when Jokeriklubin Tuki ry. sold its rights to play in SM-liiga to Jokeri-Hockey Ltd. 1988, nowadays Jokerit in KHL (Aalto, Seppo, 1992). Unlike in Sweden, there is no 51-percent rule in Finland – no restrictions on ownership – and none of the clubs´ in SM-liiga (all are Ltd:s) are a public limited company (Plc.) registered for trade on the Helsinki stock market. The Finnish development can be explained by historical reasons – fragmented Finnish sport. According to law professor Heikki Halila, the Finnish Sport Confederation could during the 90s not influence or regulate the development like the Swedish Sport Confederation in Sweden (Backman, Jyri, 2012).

In the table below, corporation in the Finnish premier league (SM-liiga) season 2017/2018 will be displayed. The table shows which of the SM-liiga clubs who are part or wholly owned by a Ltd. All SM-liiga clubs also own a share in Ice Hockey´s SM-liiga Ltd. The reader should keep in mind that ownership can change and vary.

|

Mother company: Non-profit sports club, registered association (ry./rf.) (not translated) |

Ltd.´s that runs elite ice hockey (translated) |

Ltd. without owner restrictions |

Whole/and/or part owned Ltd.´s and holding company´s |

|

|

Turun Palloseura ry. (Turku) |

HC TPS Turku Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Porin Ässät ry. (Pori) |

HC Ässät Pori Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Vaasan Sport Ry-Vasa Sport rf. (Vaasa) |

Hockey Team Vaasan Sport Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Hämeenlinnan Pallokerho ry. (Hämeenlinna) |

HPK Liiga Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Ilves ry. (Tampere) |

Ilves-Hockey Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Idrottsföreningen Kamraterna Helsingfors (I.F.K. Helsinki) rf. |

Ice Hockey Ltd. HIFK-Hockey Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Mikkelin Jukurit ry. (Mikkeli) |

Jukurit HC Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

JyP-77 ry. (Jyväskylä) |

JYP Jyväskylä Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Kalevan Pallo (KalPa) ry. (Kuopio) |

KalPa Hockey Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Kouvolan Kiekko-65 ry. (Kouvola) |

KooKoo Hockey Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Reipas Lahti ry. (Lahti) |

Lahden Pelicans Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Saimaan Pallo – SaiPa ry. (Lappeenranta) |

Liiga-SaiPa Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Rauman Lukko ry. (Rauma) |

Rauman Lukko Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Liiga-Tappara ry. (Tampere) |

Tamhockey Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

|

Oulun Kärpät 46 ry. (Oulu) |

Oulun Kärpät Ltd. |

X |

X |

|

Corporation in the Finnish premier league SM-liiga season 2017/2018 (X = yes, - = no).

The trend is clear. Corporation is the norm within SM-liiga, although none of the Ltd.’s are a public limited company (Plc.) registered for trading on the stock market. All ice hockey Ltd.´s are also wholly or partly owned by other Ltd.´s (subsidiaries).

Conclusion

Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey has both similarities and differences in the process of professionalization and commercialization. One similarity from a commercial point of view is that corporation is a relatively new phenomenon that began at the same time in the 90s through inspiration from the cooperation between Swedish-Finnish sports law associations, a time of sharp rising stock prices. One difference, however, is that there is no 51-percent rule in Finnish ice hockey like Swedish ice hockey. The main reason for the different paths representatives for Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey has chosen is the organization of sports. Representatives of Finnish elite ice hockey chose to go their own way in the 70s, meanwhile Swedish sport is characterized by consensus. The main reason for this decision was that the representatives of Finnish elite ice hockey did not think that small clubs and sport federations should affect their activities.

A key factor in the development of corporation in Swedish sport is that the Swedish Sport Confederation, since its establishment in 1903, have been governing body for Swedish sport movement. A effect of this is that Swedish sport was long characterized by deprecation against professionalization and commercialization. At the same time, a market transformation of Swedish society occurred in the 1980s and 90s. It was during this time that the Swedish elite ice hockey was transformed into a more market-oriented business. The consensus character, however, is confirmed by the fact that the Swedish Sport Confederation decided on a couple of occasions that the 51-percent rule should remain. A question that arises in this context is why representatives of the Swedish elite ice hockey clubs did not choose to go their own way in the 90s, or on latter occasions. The answer to this is that the consensus tradition is strong in Swedish sport movement and the hegemonic position the Swedish Sport Confederation has over Swedish sport. One opinion that could arise in this context is that it would be rational to abandon the 51-percent rule. By separating non-profit and commercial activities, business logic could be fully implemented. However this is not the case in Sweden, at least not yet.

References

- Aalto, Seppo (1992), Jokerit liukkaalla jäällä – 25 vuotta Jokeri-kiekkoa (Jokerit on slippery ice – 25 years of Jokerit-hockey, own translation), Gummerus, Jyväskylä

- Backman, Jyri (2012), I skuggan av NHL: En organisationsstudie av svensk och finsk elitishockey (In the shade of NHL: A organizational study of Swedish and Finnish elite ice hockey, own translation), Licentiate thesis, Gothenburg University.

- EY (2016), Hur mår svensk elitishockey? En analys av den finansiella ställningen i SHL (How healthy is Swedish elite ice hockey? An analysis of the financial position, own translation) in ey.com, published 2016-12-21 and retrieved 2017-08-22 from http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/Hur-mar-svensk/$FILE/EY_%20Sport%20Business_Hockey_LR.pdf

- Honkavaara, Aarne (1978), ”Menneet vuodet” (Lost years, own translation) in Honkavaara, Aarne, Laelma, Jyrki, Stubb, Göran, Sulkava, Esa sekä Lindroos, Hannu ja Rinne, Veikko (1978), Siniviivalla: Suomalaisen jääkiekkoilun kuumat vuodet (On Blue line: Finnish ice hockey’s hot years, own translation), Suomen Jääkiekkoliitto and Weilin+Göös, Espoo.

- KPMG (2015), Jääkiekon vaikutus Suomen talouteen ja työllisyyteen (Ice hockey’s effect on Finland’s economy and work life, own translation), Helsinki, in kpmg.com/fi/sport, published in April 2015 and retrieved 2016-06-23 from https://www.kpmg.com/FI/fi/toimialat/terveydenhuolto/Documents/Jaakiekon-vaikutus-Suomessa-2015.pdf

- Lämsä, Jari (2015), ”(Elite) sport in Finland; Trends, resources and organization” in JAMK:n sport Business opiskelijoille 2.11.2015, KIHU – Research institute for Olympic Sports, retrieved 2017-07-01 from http://energia.kihu.fi/tuotostiedostot/julkinen/2015_lms_elitesport_sel50_65824.pdf

- Lämsä, Jari (2017), ”Threatend Legitimacy: Stakeholders Criticism Towards The Finnish Olympic Committee”, The 25th EASM Conference, Bern and Magglingen, Switzerland, 5–9 september 2017, Book of Abstracs, [ed. Ströbl, Tim, et al.], pp.82–83.

- Malmsten, Krister och Pallin, Christer (2005), Idrottens föreningsrätt (Sports law, own translation), Norstedts, Stockholm.

- Mennander, Ari and Mennander, Pasi (2003), Leijonien tarina: Suomen Jääkiekkoliiton historia 1929–2004 (Lions history: The Finnish Ice Hockey Federations history 1929–2004, own translation), Ajatus Kirjat, Helsinki.

- Mesikämmen, Jani (2001), ”From Part-time Passion to Big-time Business: The Professionalization of Finnish Ice Hockey” in Howell D. Colin [ed.] (2011), Putting it in Ice, Volume II: Internationalizing ´Canada´s Game´, Gorsebrook Research Institute, Saint Mary´s University, Halifax.

- Otila, Jyrki (1989), ”Tästä se alkoi” (It started from this, own translation) in Kaukalon leijonat – Suomalaista jääkiekkoa 60 vuotta (The Lions of the Rink – Finnish ice hockey 60 years, own translation), US-Mediat, Rauma.

- Stark, Janne [red.] (1997), Svensk Ishockey 75 år: ett jubileumsverk i samband med Svenska Ishockeyförbundets 75-års jubileum, Del II, Faktadelen (Swedish ice hockey 75 years: an anniversary book in conjunction with the Swedish ice Hockey Federations 75 year anniversary, Part II, Fact, own translation) Strömberg/Brunnhage, Vällingby.

- Stark, Tobias (2010), Folkhemmet på is: Ishockey, modernisering och nationell identitet i Sverige 1920–1972, (Folkhemmet on ice, Ice hockey, modernization and national identity in Sweden 1920–1972, own translation), Diss. Linnéuniversitetet, Idrottsforum, Malmö.

Swedish and Finnish sport movement (printed material)

Finland

Finnish government sport council

Finnish Ice Hockey Federation

Finnish Olympic Committee

Valo (Finland´s National Sport Organization)

Sweden

Swedish Ice Hockey Federation

Swedish Sport Confederation

Newspapers and Magazines

Expressen

Hockey: Officiellt organ för Svenska Ishockeyförbundet

Kauppalehti

Conference presentation

Lämsä, Jari (2017b), ”Threatend Legitimacy: Stakeholders Criticism Towards The Finnish Olympic Committee” in The 25th EASM Conference, Bern and Magglingen, Switzerland, 5–9 September 2017.

Home pages

Statistics Finland, www.stat.fi

Statistics Sweden, www.scb.se

Guillaume Bodet, Professor of Sport Marketing and Management at the School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, at the Univ Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon-1, L-VIS, (France)

Alan Gaudefroy, Univ Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon-1, L-VIS, (France)

Guillaume Routier, Univ Lyon, University Claude Bernard Lyon-1, L-VIS, (France)

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the French Ice Hockey Federation (FFHG) for their support in the data collection.

Who are they?

A focus on French ice-hockey participants’ profiles